A Reloading Testing Process

By Matthew Cameron

The reloading process we call load development, in my opinion, consists of two distinct phases that may be described as the research and development phase and secondly the shooting phase. In the first instance we choose the cartridge and projectile to suit the task we have set out to achieve followed by the choice of powder and primer. Conversely we may attempt to adapt a rifle we already own by changing the type of bullet and/or its weight. The type of game we intend to hunt will have a huge influence on these decisions.

We should keep an open mind when researching and remember that everything you will read is the singular opinion of a particular author that may be balanced by actual use of stated components. By researching over the widest possible field you should be able to arrive at a reasonable viewpoint. However you should be aware that the reloading shooting press is not always 100 % correct in its opinions.

Reloading And The Internet

The greatest asset available to reloaders today is the internet. The amount of free reloading data available is simply staggering. No matter what the cartridge it will have appeared on the internet somewhere.

Simply typing in the cartridge name on a search engine will provide initial information that you might require and probably lead to other useful sites. This does not include specific sites dealing with reloading and associated subjects.

The second, shooting phase will be influenced by the selection and quality of reloading components we have made in phase one. If we make incorrect or questionable choices initially, how will this affect the accuracy of what we might achieve in phase two? What do we need to do to ensure some consistent results? Even if phase one is totally accurate where is the logical set routine or process to shoot the loads we have to test? If one exists the author is yet to read about it. Whilst there are industry specifications relating to chamber dimensions and maximum ammunition pressures there is nothing that I can find about the actual shooting.

Are there in fact any reloading standards that the average reloader can aim for (no pun intended!) to ensure some consistent results? In my opinion such standards do not exist. What we have is a large volume of opinion and generally accepted practice but nothing that is spelt out in detail. Further, ammunition & powder companies tend to use universal receivers for testing reloading components. How do the results obtained relate to factory production rifles?

If different companies did the same initial reloading development I do not think that they would shoot and clean the barrel in the same manner. Surely this would affect the results obtained. In addition where such a rifle was shot would also have some bearing on the final outcome.

A reloader on the coast would have different figures from a reloader who lives three thousand feet above sea level in a different geographic location. Where are the computer programs to reduce all such figures to a common data base at standard atmospheric pressure and temperature? However the same problems must be encountered by the powder and bullet manufacturers who develop multiple loads for each cartridge type. Is this one reason why there is such a wide variation in the loads listed in the various reloading manuals?

Yes, I am well aware that all rifles and barrels are individuals, and this causes enormous problems when trying to come up with acceptable reloading standards. The starting point has to be a chamber and barrel cut to industry specifications. Somewhere in my files I have the results of a gunsmith's test on two identical rifles whose chambers were cut one after another with the same reamer.

The third successive cut was a set of in line reloading dies. Load development in the first rifle was normal and expected.

The second rifle blew primers when the same upper loads were fired. The gunsmith checked all the dimensions, perfect; he couldn't work it out either.

There are a host of other variables that may or may not affect the results that you obtain. For the sake of discussion, do you shoot three or five shoot groups over the chronograph. Will a new rifle require a different shooting technique to "break in" a new barrel; will such a process influence the final outcome?

My personal option is to shoot three shot groups, a statement that will no doubt cause headshaking by some who read this. Whenever this subject is raised those in favour of five shot groups mutter something about statistics and then move on. This raises another question.

Who decided that five shots groups should be the norm? Why not ten shot groups? Perhaps twenty! Could there be other reasons why five shot groups are larger than three shot groups? Could it possibly be that the speed of shooting causes extra barrel heating. Further, what about the increased amount of barrel fouling caused by the extra shots? In any particular rifle when exactly, do groups start to "open up" due to barrel fouling?

What I am suggesting is that five shot groups are nothing more than accepted opinion. Yes there are a lot of questions but if we are to achieve any meaningful results they do, I suggest, need to be investigated and answered.

The evidence of twenty five years of hand loading leads me to suggest that after ten shots, in some rifles, barrel fouling will cause a measurable increase of group size This increase would be of concern to a benchrest shooter, possibly to a long range shooter but not worry a hunter after bigger game. Is this the reason that bench rest shooters frequently clean their match grade, lapped barrels?

In addition the amount of fouling is, in my opinion, affected by the type of barrel steel. Is your cleaning process valid and consistent for a particular type of steel? It is possible that my current frequency of cleaning is, for testing purposes, incorrect. If we are really serious should we clean the barrel after each group to apply a further consistency to the testing process?

Is your barrel clean to start with? Are you sure that the group you shoot is reflecting the performance of the rifle and ammunition? Are you, the rifleman, sufficiently experienced to call each shot?

Is there in fact a solution that will allow for these variables so that the result obtained is meaningful? Do different powder and ammunition companies use the same standards to develop loads? Are there in fact any written standards?

Wind velocity is a constant problem that may be overcome by shooting either very early or very late in the day. If you do this it may cause chronograph problems. Temperature may also cause problems at a later time. If you have developed a load that does not exhibit pressure signs in winter there is no guarantee that it will be safe to use in the heat of summer.

Let us assume that you have a rifle with a clean barrel and a batch of suitable ammunition at a constant temperature. The morning is windless; you switch on the chronograph and begin to shoot. This raises the first question. Do you fire a single shot to "dirty up" the barrel before attempting to shoot a group? I believe that this is necessary as few rifles with a clean barrel will print a first shot in the same area as a dirty one. It may also be used to make sure that the chronograph is working correctly.

Do they always test under controlled conditions or are some of their tests outdoors? Can we, as handloaders, hope to duplicate the results that ammunition companies achieve?

Another question, just how fast do you shoot, how many shots before you stop? Are you going to let the barrel cool completely between groups? How many consecutive shots before you clean the barrel?

The following is a system that I have evolved over twenty five years. This is a person opinion and suits my requirements; it may not be suitable for you, the reader. However it has produced reliable accurate ammunition to my standards, consistently.

Load a minimum of three/five cases for each powder load, usually five different charge weights is sufficient, working from the lowest load. Increase powder charges by 1/2 grain, or if a smaller case, 1/3 grain increments for each load. Firing commences with the extracted/calculated minimum powder charge shooting over the chronograph. As the powder charges increase the group size should tighten up as you approach a specific load, usually below the maximum.

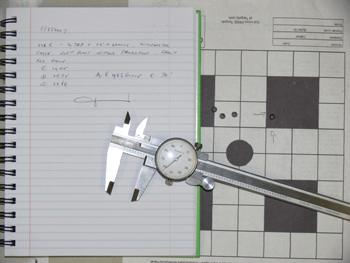

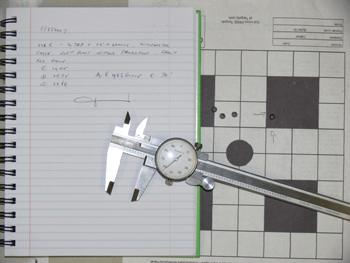

Having reached this peak the group will tend to increase in size. This optimum should be shot several times to confirm that the original was not mere chance. Each shot is fired at a comfortable pace without excessive haste. All shots that are "pulled" should be noted. Records should be kept of group size and average velocity.

After each three/five shot group the rifle is removed into the shade and the barrel is allowed to cool to ambient temperature.

The barrel is cleaned whilst warm at the end of each nine shots (three shot groups), or each ten shots for five shot groups. I believe that it is important to use the same cleaning procedure after each group or groups. Once the wind starts, even the faintest breeze, stop shooting. I will admit that I am not experienced enough to read the wind, very few shooter's are. Accumulated data needs to be recorded as shooting is likely to be spread over several days.

In addition to short term needs such data can be useful at a later date and can prevent repetition. Be aware that there will be some variation in velocity with changing temperatures. If you have shot, say five groups, there will be sufficient initial data to indicate if you should proceed with this powder. If the groups are not getting smaller and if the increased powder charges are producing rapidly decreasing velocity gains I would suggest that it is time to consider another powder. You will have to re-shoot the whole process. I am assuming that you will continue to use the same projectile and primer. Large variations in velocity may be caused by low loading density.

It is obvious that most factory cartridges are flexible about the type of powder used whilst some wildcat designs are a little more stringent in their powder requirements. There are good reasons for this state of affairs.

When developed many of these designs lacked the two vital items that made them, equal to, or better than factory cartridges of similar size and capacity. They were heavy projectiles in relation to calibre and slow burning powders to propel them.

Remember each rifle is a law unto itself. Should the chronograph show velocities well below averaged book values, a further one or two increases in powder charges may be justified. You just need to proceed with caution and look for realistic values. Added velocity is useless if groups continue to grow in size.

Actual velocities compared with averaged book values will indicate when you are approaching maximum loads for that rifle, plus of course all of the usual pressure signs. If you are comfortable with your initial results they need to be confirmed by at least a further two groups of the best load, again in windless conditions.

I do not claim that my particular process is better than any other. It is merely a starting point to develop a system that you are comfortable with. Three important points.

If you are going to do a lot of load testing a chronograph is, I suggest, vitally important, without one you are just guessing. Mine is a plain vanilla model that only gives velocity, nothing more. It is sufficient for the task required.

Secondly, a good ballistic computer program is, I suggest, also a requirement. And finally, if meaningful results are to be obtained keep accurate records.

I came across the following in an old issue of Handloader magazine that seems to sum up the whole process of testing rifles and ammunition. No 6. Page 57. "Too often assumptions are accepted as fact simply because no other reason is apparent. This I feel is a mistake. To speculate is one thing, to make a statement of fact is quite another".

Shoot safely.

Matthew Cameron is a retired Australian Airline Pilot who flew domestically within Australia and Internationally out of South East Asia. Interested in long range varminting and pig shooting for many years, he reloads for a variety of calibres and has written articles on reloading and associated subjects since the early 1990's, published in Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. In the last few years he has enjoyed bench rest shooting and gliding when not reloading or writing.

By Matthew Cameron

The reloading process we call load development, in my opinion, consists of two distinct phases that may be described as the research and development phase and secondly the shooting phase. In the first instance we choose the cartridge and projectile to suit the task we have set out to achieve followed by the choice of powder and primer. Conversely we may attempt to adapt a rifle we already own by changing the type of bullet and/or its weight. The type of game we intend to hunt will have a huge influence on these decisions.

We should keep an open mind when researching and remember that everything you will read is the singular opinion of a particular author that may be balanced by actual use of stated components. By researching over the widest possible field you should be able to arrive at a reasonable viewpoint. However you should be aware that the reloading shooting press is not always 100 % correct in its opinions.

Reloading And The Internet

The greatest asset available to reloaders today is the internet. The amount of free reloading data available is simply staggering. No matter what the cartridge it will have appeared on the internet somewhere.

Simply typing in the cartridge name on a search engine will provide initial information that you might require and probably lead to other useful sites. This does not include specific sites dealing with reloading and associated subjects.

The second, shooting phase will be influenced by the selection and quality of reloading components we have made in phase one. If we make incorrect or questionable choices initially, how will this affect the accuracy of what we might achieve in phase two? What do we need to do to ensure some consistent results? Even if phase one is totally accurate where is the logical set routine or process to shoot the loads we have to test? If one exists the author is yet to read about it. Whilst there are industry specifications relating to chamber dimensions and maximum ammunition pressures there is nothing that I can find about the actual shooting.

Are there in fact any reloading standards that the average reloader can aim for (no pun intended!) to ensure some consistent results? In my opinion such standards do not exist. What we have is a large volume of opinion and generally accepted practice but nothing that is spelt out in detail. Further, ammunition & powder companies tend to use universal receivers for testing reloading components. How do the results obtained relate to factory production rifles?

If different companies did the same initial reloading development I do not think that they would shoot and clean the barrel in the same manner. Surely this would affect the results obtained. In addition where such a rifle was shot would also have some bearing on the final outcome.

A reloader on the coast would have different figures from a reloader who lives three thousand feet above sea level in a different geographic location. Where are the computer programs to reduce all such figures to a common data base at standard atmospheric pressure and temperature? However the same problems must be encountered by the powder and bullet manufacturers who develop multiple loads for each cartridge type. Is this one reason why there is such a wide variation in the loads listed in the various reloading manuals?

Yes, I am well aware that all rifles and barrels are individuals, and this causes enormous problems when trying to come up with acceptable reloading standards. The starting point has to be a chamber and barrel cut to industry specifications. Somewhere in my files I have the results of a gunsmith's test on two identical rifles whose chambers were cut one after another with the same reamer.

The third successive cut was a set of in line reloading dies. Load development in the first rifle was normal and expected.

The second rifle blew primers when the same upper loads were fired. The gunsmith checked all the dimensions, perfect; he couldn't work it out either.

There are a host of other variables that may or may not affect the results that you obtain. For the sake of discussion, do you shoot three or five shoot groups over the chronograph. Will a new rifle require a different shooting technique to "break in" a new barrel; will such a process influence the final outcome?

My personal option is to shoot three shot groups, a statement that will no doubt cause headshaking by some who read this. Whenever this subject is raised those in favour of five shot groups mutter something about statistics and then move on. This raises another question.

Who decided that five shots groups should be the norm? Why not ten shot groups? Perhaps twenty! Could there be other reasons why five shot groups are larger than three shot groups? Could it possibly be that the speed of shooting causes extra barrel heating. Further, what about the increased amount of barrel fouling caused by the extra shots? In any particular rifle when exactly, do groups start to "open up" due to barrel fouling?

What I am suggesting is that five shot groups are nothing more than accepted opinion. Yes there are a lot of questions but if we are to achieve any meaningful results they do, I suggest, need to be investigated and answered.

The evidence of twenty five years of hand loading leads me to suggest that after ten shots, in some rifles, barrel fouling will cause a measurable increase of group size This increase would be of concern to a benchrest shooter, possibly to a long range shooter but not worry a hunter after bigger game. Is this the reason that bench rest shooters frequently clean their match grade, lapped barrels?

In addition the amount of fouling is, in my opinion, affected by the type of barrel steel. Is your cleaning process valid and consistent for a particular type of steel? It is possible that my current frequency of cleaning is, for testing purposes, incorrect. If we are really serious should we clean the barrel after each group to apply a further consistency to the testing process?

Is your barrel clean to start with? Are you sure that the group you shoot is reflecting the performance of the rifle and ammunition? Are you, the rifleman, sufficiently experienced to call each shot?

Is there in fact a solution that will allow for these variables so that the result obtained is meaningful? Do different powder and ammunition companies use the same standards to develop loads? Are there in fact any written standards?

Wind velocity is a constant problem that may be overcome by shooting either very early or very late in the day. If you do this it may cause chronograph problems. Temperature may also cause problems at a later time. If you have developed a load that does not exhibit pressure signs in winter there is no guarantee that it will be safe to use in the heat of summer.

Let us assume that you have a rifle with a clean barrel and a batch of suitable ammunition at a constant temperature. The morning is windless; you switch on the chronograph and begin to shoot. This raises the first question. Do you fire a single shot to "dirty up" the barrel before attempting to shoot a group? I believe that this is necessary as few rifles with a clean barrel will print a first shot in the same area as a dirty one. It may also be used to make sure that the chronograph is working correctly.

Do they always test under controlled conditions or are some of their tests outdoors? Can we, as handloaders, hope to duplicate the results that ammunition companies achieve?

Another question, just how fast do you shoot, how many shots before you stop? Are you going to let the barrel cool completely between groups? How many consecutive shots before you clean the barrel?

The following is a system that I have evolved over twenty five years. This is a person opinion and suits my requirements; it may not be suitable for you, the reader. However it has produced reliable accurate ammunition to my standards, consistently.

Load a minimum of three/five cases for each powder load, usually five different charge weights is sufficient, working from the lowest load. Increase powder charges by 1/2 grain, or if a smaller case, 1/3 grain increments for each load. Firing commences with the extracted/calculated minimum powder charge shooting over the chronograph. As the powder charges increase the group size should tighten up as you approach a specific load, usually below the maximum.

Having reached this peak the group will tend to increase in size. This optimum should be shot several times to confirm that the original was not mere chance. Each shot is fired at a comfortable pace without excessive haste. All shots that are "pulled" should be noted. Records should be kept of group size and average velocity.

After each three/five shot group the rifle is removed into the shade and the barrel is allowed to cool to ambient temperature.

The barrel is cleaned whilst warm at the end of each nine shots (three shot groups), or each ten shots for five shot groups. I believe that it is important to use the same cleaning procedure after each group or groups. Once the wind starts, even the faintest breeze, stop shooting. I will admit that I am not experienced enough to read the wind, very few shooter's are. Accumulated data needs to be recorded as shooting is likely to be spread over several days.

In addition to short term needs such data can be useful at a later date and can prevent repetition. Be aware that there will be some variation in velocity with changing temperatures. If you have shot, say five groups, there will be sufficient initial data to indicate if you should proceed with this powder. If the groups are not getting smaller and if the increased powder charges are producing rapidly decreasing velocity gains I would suggest that it is time to consider another powder. You will have to re-shoot the whole process. I am assuming that you will continue to use the same projectile and primer. Large variations in velocity may be caused by low loading density.

It is obvious that most factory cartridges are flexible about the type of powder used whilst some wildcat designs are a little more stringent in their powder requirements. There are good reasons for this state of affairs.

When developed many of these designs lacked the two vital items that made them, equal to, or better than factory cartridges of similar size and capacity. They were heavy projectiles in relation to calibre and slow burning powders to propel them.

Remember each rifle is a law unto itself. Should the chronograph show velocities well below averaged book values, a further one or two increases in powder charges may be justified. You just need to proceed with caution and look for realistic values. Added velocity is useless if groups continue to grow in size.

Actual velocities compared with averaged book values will indicate when you are approaching maximum loads for that rifle, plus of course all of the usual pressure signs. If you are comfortable with your initial results they need to be confirmed by at least a further two groups of the best load, again in windless conditions.

I do not claim that my particular process is better than any other. It is merely a starting point to develop a system that you are comfortable with. Three important points.

If you are going to do a lot of load testing a chronograph is, I suggest, vitally important, without one you are just guessing. Mine is a plain vanilla model that only gives velocity, nothing more. It is sufficient for the task required.

Secondly, a good ballistic computer program is, I suggest, also a requirement. And finally, if meaningful results are to be obtained keep accurate records.

I came across the following in an old issue of Handloader magazine that seems to sum up the whole process of testing rifles and ammunition. No 6. Page 57. "Too often assumptions are accepted as fact simply because no other reason is apparent. This I feel is a mistake. To speculate is one thing, to make a statement of fact is quite another".

Shoot safely.

Matthew Cameron is a retired Australian Airline Pilot who flew domestically within Australia and Internationally out of South East Asia. Interested in long range varminting and pig shooting for many years, he reloads for a variety of calibres and has written articles on reloading and associated subjects since the early 1990's, published in Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. In the last few years he has enjoyed bench rest shooting and gliding when not reloading or writing.