Reloading - Looking After The Brass Cartridge Case

By Matthew Cameron

The brass cartridge case is manufactured on several continents with varying degrees of quality control. When purchasing brass for your particular rifle needs, be aware that quality varies, even between calibres of the same make.

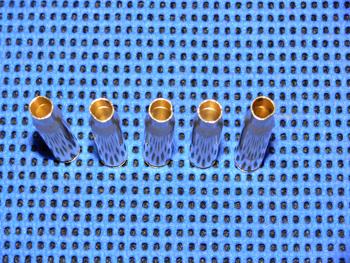

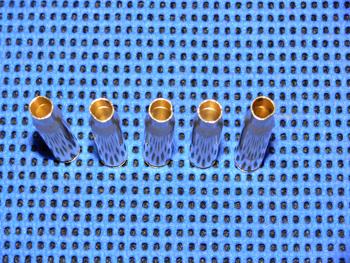

Various mouth defects in new brass cases.

Of all the items associated with shooting and its various disciplines the brass cartridge case is, in my opinion, the item least thought of. Ask any shooter about his new rifle or telescopic sight and he will wax lyrical. Ask him how he looks after his brass and you will be met with a blank stare. With about 50,000 lbs. plus of force per square inch close to your face when you pull the trigger, you should treat your brass with some respect. The quality control that you exercise when reloading will reflect on your rifle's accuracy and cartridge case life. What follows is one opinion on quality control. You may not agree.

Various case defects. Last is incipient head separation.

We should start at the beginning; i.e. new brass cartridge cases. My personal preference is to buy in bulk lots of 100 cases, however this may not suit individual requirements. Perhaps it is preferable to buy more rather than less. Whilst of high quality they are not yet perfect and need attention before you start to load them. In this day and age, it is almost impossible to purchase poor quality components that are used in reloading. Stick with the recognized brands and you cannot go wrong.

Various mouth defects in new brass cases.

If you inspect the case mouths you will invariably find some that are out of round. As a first item, I lubricate all cases and run them through the normal sizing die. When you have finished this, you now have a base line to work from. You should also wish to check the overall length. They should all be the same. However, in my experience you will have to trim them to achieve this. Rule Number 1 is never assume anything.

The next item on the agenda is primer pockets. I have never found a perfectly flat one in new brass; there is always a radius between the bottom of the pocket and the side wall.

This tool cleans up primer pockets-outside.

The small tool that is usually called a primer pocket uniformer will remove the high spots in the pocket and make a flat bed to insert the primer on. This tool is also useful after the cartridge has been fired to remove some primer residue. It is, in my opinion, important to keep primer pockets in pristine condition to ensure perfect ignition every time you pull the trigger. The design of this small tool limits the depth of the primer pocket to the design specifications.

This tool cleans up primer pockets-inside.

The next step is to use a small chamfering tool to remove all the imperfections around the case mouth both inside and out. The inside chamfer starts the bullet into the case mouth, of particular importance when using flat base bullets.

For normal hunting cartridges this is about as far as I go to prepare brass, from this point on, it is only necessary to keep the cases and primer pockets clean. It is very important to check the overall length of the case about every 4 or 5 firings depending on calibre.

Some older case designs will stretch quite quickly if fired using near maximum loads. There are tables available that show maximum and trim lengths. For many reasons these should be adhered to.

It is necessary to continually check case length.

If the case exceeds the maximum length, it may not chamber. This could be very inconvenient, and could cost you a trophy animal. It is also possible that if it fits in the chamber you may be faced with greatly increased pressures.

Once loaded, cartridges should be kept in suitable containers for transport and then if necessary transferred to a cartridge belt or other device if you have to do a lot of walking after game. As long as the rounds are protected from outside influences and are separated from one another, just about any type of case will do. Plastic, cardboard or combinations thereof seem to be most popular. At this point, we come to a parting of the ways as to whether we treat brass any further, and if in fact it achieves any useful purpose.

Brass should be stored in plastic or cardboard containers.

There are two distinct schools of thought. The first says that to do so is a waste of time, particularly if the rifle concerned is a stock standard factory offering. The second path relates to a rifle custom built to benchrest standards. In this case there is no argument. Brass HAS to be further treated if you wish to obtain the best results.

We left our cartridge case that had the primer pocket reamed, the neck chamfered inside and out, its length checked and a run through the normal sizing die.

Run new brass through the reloading die.

For some factory rifles it is possible that the next steps may assist in improving accuracy. The types of rifles that I am referring to are those factory rifles that are used for varmint shooting. We are looking at the various .22 calibre offerings and .243 calibre also.

With custom rifles built to benchrest standards, the turning of case necks to specified thicknesses is a requirement. This situation applies to pure benchrest rifles, as well as some rifles built to target live game at long distances.

Normal cases will not chamber in rifles that have tight necks.

The argument is that to carry out this procedure on a factory rifle is a waste of time as the greater tolerances within the rifles chamber will negate the advantages of this step. I am not so sure that this is totally correct. The accuracy buffs will claim that if the neck is not totally concentric, the bullet will tend towards the thin side of the case when the rifle is fired. Some recent experiments in the US indicate that even partial neck turning is beneficial to accuracy in a variety of calibres.

The requirement is to remove just enough brass to ensure that the case necks are as concentric as possible. For my .243 cases, the neck turning tool was set with a feeler gauge at .015 inches. It would not remove brass anywhere along the neck, and at .014 it started to cut. Every case left some uncut areas, usually at the neck mouth, the worst for a distance of 2 mm. Some cases were oval in shape and left uncut areas on either side.

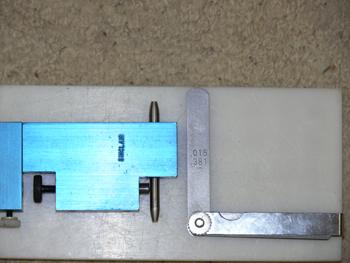

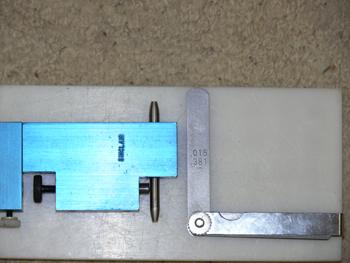

Neck turning tool and feeler gauge.

You have to be careful and ensure that when you set the tool up you do not cut into the shoulder of the case.

During the manufacturing process the primer pocket flash hole is punched in the base of the cartridge case. It should be in the centre of the pocket. If not, discard the case. This process can also leave a small amount of brass protruding into the case surrounding the flash hole. This may have an effect on powder ignition. A small tool will remove this excess brass, leaving a small inner bevel.

Having arrived at this stage of case preparation, there is one item remaining. Accuracy buffs weigh cases and discard those that are out of the range. The theory is simple enough. If a case has the same external dimensions and heavier weight, the internal volume must be less and hence pressure will be higher when fired. The difference in velocity will affect accuracy.

The author prefers to buy brass in bulk.

As an example, I picked a number of 220 Swift cases at random. They were weighed and averaged. A plus or minus 1% variation applied to all cases and less than 3% were discarded. This, in my opinion, is good quality control for standard commercial cases. Depending on the brand, the discard rate may be lower. One European brand had a zero rejection rate in relation to weight in one calibre.

It is all very well to prepare brass in this fashion but it is also necessary to keep it clean. There is an old saying in hydraulics that cleanliness is godliness and it can also apply to cartridge cases. A dirty case can affect your rifle's chamber and your reloading dies.

In the days when it was legal to own self loading rifles I can recall several occasions when a Ruger Mini 14 jammed due to dirty ammunition and poor rifle cleaning practices. Of greater concern at the time was the live round stuck in the chamber.

There are many ways of cleaning cartridge cases; my personal preference is to use liquids. Several commercial cleaners are available, however I prefer to use the following. There are variations on the theme but is can be done quite cheaply. After cases are lubricated and run through the sizing die, rinse the cases in industrial thinners or acetone and then rinse at least twice in fresh water.

Dirty, clean and polished brass.

If cases are dirty, soak them in a solution of white vinegar and detergent (2 tablespoons of detergent to 1/2 litre of vinegar) overnight. Some make the solution hot and others add a teaspoon of common salt. Rinse again before the next phase.

To get some shine back on the cases soak them in a solution of fresh water and Cream of Tartar (1 tablespoon to 1/2 litre of water) for about four hours. Rinse at least twice in clean water and allow to air dry. Neither step is an every time item; just make sure that they are clean. It is important to note that there is a difference between clean and shiny brass.

If you want to shine your brass, another alternative is to tumble the cases using walnut shells as a polishing medium: a cheap and simple method.

The hardest part of the case to keep clean is the neck area that has powder and primer residue. This black accumulation is tough to remove, and the above steps are not always successful. To really clean up this area, my preferred method is to use a household cleaning cloth, with the addition of brake cleaner or carburetor cleaner. Hold the cloth between thumb and forefinger and rotate the neck. The cleaner should leave the neck squeaky clean and bright. The cloths are easily obtainable at your local supermarket, and may be washed when dirty. If this fails, perhaps you may have to resort to using very fine steel wool.

Some of the tools used in brass preparation.

You will note that what we have carried out are a series of small improvements to the basic case, history has shown that these small differences do have an effect on group size.

To the average hunter there are not of importance. To anyone who shoots at long range for whatever reason, they are, in my opinion, worthwhile steps. Aside from constantly checking the overall length and cleaning, the rest of the steps are one off items. Depending on the steps you decide to take, preparation of brass may be a time consuming lengthy process. Usually I tend to carry out this procedure during the months when shooting or hunting is slow.

In my opinion, keeping your brass in pristine condition is not difficult, and is time well spent.

Matthew Cameron is a retired Australian Airline Pilot who flew domestically within Australia and internationally out of Southeast Asia. Interested in long range varminting and pig shooting for many years, he reloads for a variety of calibres and has written articles on reloading and associated subjects since the early 1990's, published in Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. In the last few years he has enjoyed bench rest shooting and gliding when not reloading or w

By Matthew Cameron

The brass cartridge case is manufactured on several continents with varying degrees of quality control. When purchasing brass for your particular rifle needs, be aware that quality varies, even between calibres of the same make.

Various mouth defects in new brass cases.

Of all the items associated with shooting and its various disciplines the brass cartridge case is, in my opinion, the item least thought of. Ask any shooter about his new rifle or telescopic sight and he will wax lyrical. Ask him how he looks after his brass and you will be met with a blank stare. With about 50,000 lbs. plus of force per square inch close to your face when you pull the trigger, you should treat your brass with some respect. The quality control that you exercise when reloading will reflect on your rifle's accuracy and cartridge case life. What follows is one opinion on quality control. You may not agree.

Various case defects. Last is incipient head separation.

We should start at the beginning; i.e. new brass cartridge cases. My personal preference is to buy in bulk lots of 100 cases, however this may not suit individual requirements. Perhaps it is preferable to buy more rather than less. Whilst of high quality they are not yet perfect and need attention before you start to load them. In this day and age, it is almost impossible to purchase poor quality components that are used in reloading. Stick with the recognized brands and you cannot go wrong.

Various mouth defects in new brass cases.

If you inspect the case mouths you will invariably find some that are out of round. As a first item, I lubricate all cases and run them through the normal sizing die. When you have finished this, you now have a base line to work from. You should also wish to check the overall length. They should all be the same. However, in my experience you will have to trim them to achieve this. Rule Number 1 is never assume anything.

The next item on the agenda is primer pockets. I have never found a perfectly flat one in new brass; there is always a radius between the bottom of the pocket and the side wall.

This tool cleans up primer pockets-outside.

The small tool that is usually called a primer pocket uniformer will remove the high spots in the pocket and make a flat bed to insert the primer on. This tool is also useful after the cartridge has been fired to remove some primer residue. It is, in my opinion, important to keep primer pockets in pristine condition to ensure perfect ignition every time you pull the trigger. The design of this small tool limits the depth of the primer pocket to the design specifications.

This tool cleans up primer pockets-inside.

The next step is to use a small chamfering tool to remove all the imperfections around the case mouth both inside and out. The inside chamfer starts the bullet into the case mouth, of particular importance when using flat base bullets.

For normal hunting cartridges this is about as far as I go to prepare brass, from this point on, it is only necessary to keep the cases and primer pockets clean. It is very important to check the overall length of the case about every 4 or 5 firings depending on calibre.

Some older case designs will stretch quite quickly if fired using near maximum loads. There are tables available that show maximum and trim lengths. For many reasons these should be adhered to.

It is necessary to continually check case length.

If the case exceeds the maximum length, it may not chamber. This could be very inconvenient, and could cost you a trophy animal. It is also possible that if it fits in the chamber you may be faced with greatly increased pressures.

Once loaded, cartridges should be kept in suitable containers for transport and then if necessary transferred to a cartridge belt or other device if you have to do a lot of walking after game. As long as the rounds are protected from outside influences and are separated from one another, just about any type of case will do. Plastic, cardboard or combinations thereof seem to be most popular. At this point, we come to a parting of the ways as to whether we treat brass any further, and if in fact it achieves any useful purpose.

Brass should be stored in plastic or cardboard containers.

There are two distinct schools of thought. The first says that to do so is a waste of time, particularly if the rifle concerned is a stock standard factory offering. The second path relates to a rifle custom built to benchrest standards. In this case there is no argument. Brass HAS to be further treated if you wish to obtain the best results.

We left our cartridge case that had the primer pocket reamed, the neck chamfered inside and out, its length checked and a run through the normal sizing die.

Run new brass through the reloading die.

For some factory rifles it is possible that the next steps may assist in improving accuracy. The types of rifles that I am referring to are those factory rifles that are used for varmint shooting. We are looking at the various .22 calibre offerings and .243 calibre also.

With custom rifles built to benchrest standards, the turning of case necks to specified thicknesses is a requirement. This situation applies to pure benchrest rifles, as well as some rifles built to target live game at long distances.

Normal cases will not chamber in rifles that have tight necks.

The argument is that to carry out this procedure on a factory rifle is a waste of time as the greater tolerances within the rifles chamber will negate the advantages of this step. I am not so sure that this is totally correct. The accuracy buffs will claim that if the neck is not totally concentric, the bullet will tend towards the thin side of the case when the rifle is fired. Some recent experiments in the US indicate that even partial neck turning is beneficial to accuracy in a variety of calibres.

The requirement is to remove just enough brass to ensure that the case necks are as concentric as possible. For my .243 cases, the neck turning tool was set with a feeler gauge at .015 inches. It would not remove brass anywhere along the neck, and at .014 it started to cut. Every case left some uncut areas, usually at the neck mouth, the worst for a distance of 2 mm. Some cases were oval in shape and left uncut areas on either side.

Neck turning tool and feeler gauge.

You have to be careful and ensure that when you set the tool up you do not cut into the shoulder of the case.

During the manufacturing process the primer pocket flash hole is punched in the base of the cartridge case. It should be in the centre of the pocket. If not, discard the case. This process can also leave a small amount of brass protruding into the case surrounding the flash hole. This may have an effect on powder ignition. A small tool will remove this excess brass, leaving a small inner bevel.

Having arrived at this stage of case preparation, there is one item remaining. Accuracy buffs weigh cases and discard those that are out of the range. The theory is simple enough. If a case has the same external dimensions and heavier weight, the internal volume must be less and hence pressure will be higher when fired. The difference in velocity will affect accuracy.

The author prefers to buy brass in bulk.

As an example, I picked a number of 220 Swift cases at random. They were weighed and averaged. A plus or minus 1% variation applied to all cases and less than 3% were discarded. This, in my opinion, is good quality control for standard commercial cases. Depending on the brand, the discard rate may be lower. One European brand had a zero rejection rate in relation to weight in one calibre.

It is all very well to prepare brass in this fashion but it is also necessary to keep it clean. There is an old saying in hydraulics that cleanliness is godliness and it can also apply to cartridge cases. A dirty case can affect your rifle's chamber and your reloading dies.

In the days when it was legal to own self loading rifles I can recall several occasions when a Ruger Mini 14 jammed due to dirty ammunition and poor rifle cleaning practices. Of greater concern at the time was the live round stuck in the chamber.

There are many ways of cleaning cartridge cases; my personal preference is to use liquids. Several commercial cleaners are available, however I prefer to use the following. There are variations on the theme but is can be done quite cheaply. After cases are lubricated and run through the sizing die, rinse the cases in industrial thinners or acetone and then rinse at least twice in fresh water.

Dirty, clean and polished brass.

If cases are dirty, soak them in a solution of white vinegar and detergent (2 tablespoons of detergent to 1/2 litre of vinegar) overnight. Some make the solution hot and others add a teaspoon of common salt. Rinse again before the next phase.

To get some shine back on the cases soak them in a solution of fresh water and Cream of Tartar (1 tablespoon to 1/2 litre of water) for about four hours. Rinse at least twice in clean water and allow to air dry. Neither step is an every time item; just make sure that they are clean. It is important to note that there is a difference between clean and shiny brass.

If you want to shine your brass, another alternative is to tumble the cases using walnut shells as a polishing medium: a cheap and simple method.

The hardest part of the case to keep clean is the neck area that has powder and primer residue. This black accumulation is tough to remove, and the above steps are not always successful. To really clean up this area, my preferred method is to use a household cleaning cloth, with the addition of brake cleaner or carburetor cleaner. Hold the cloth between thumb and forefinger and rotate the neck. The cleaner should leave the neck squeaky clean and bright. The cloths are easily obtainable at your local supermarket, and may be washed when dirty. If this fails, perhaps you may have to resort to using very fine steel wool.

Some of the tools used in brass preparation.

You will note that what we have carried out are a series of small improvements to the basic case, history has shown that these small differences do have an effect on group size.

To the average hunter there are not of importance. To anyone who shoots at long range for whatever reason, they are, in my opinion, worthwhile steps. Aside from constantly checking the overall length and cleaning, the rest of the steps are one off items. Depending on the steps you decide to take, preparation of brass may be a time consuming lengthy process. Usually I tend to carry out this procedure during the months when shooting or hunting is slow.

In my opinion, keeping your brass in pristine condition is not difficult, and is time well spent.

Matthew Cameron is a retired Australian Airline Pilot who flew domestically within Australia and internationally out of Southeast Asia. Interested in long range varminting and pig shooting for many years, he reloads for a variety of calibres and has written articles on reloading and associated subjects since the early 1990's, published in Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. In the last few years he has enjoyed bench rest shooting and gliding when not reloading or w